We´ve all been there:

You're concentrating on an important task – *DING* * – a new message pops up. Quick read. Back to the task. A colleague comes in: “Hey, can you quickly send me this document?” Sure, you can. And then ...

“Where was I?”

And before you can even get your thoughts back together, your phone rings.

Work interruptions are part of everyday life for many people. Whether it's emails, phone calls, quick chats, or to-dos handed to you on the go. In our dynamic working world, they are usually the rule rather than the exception.

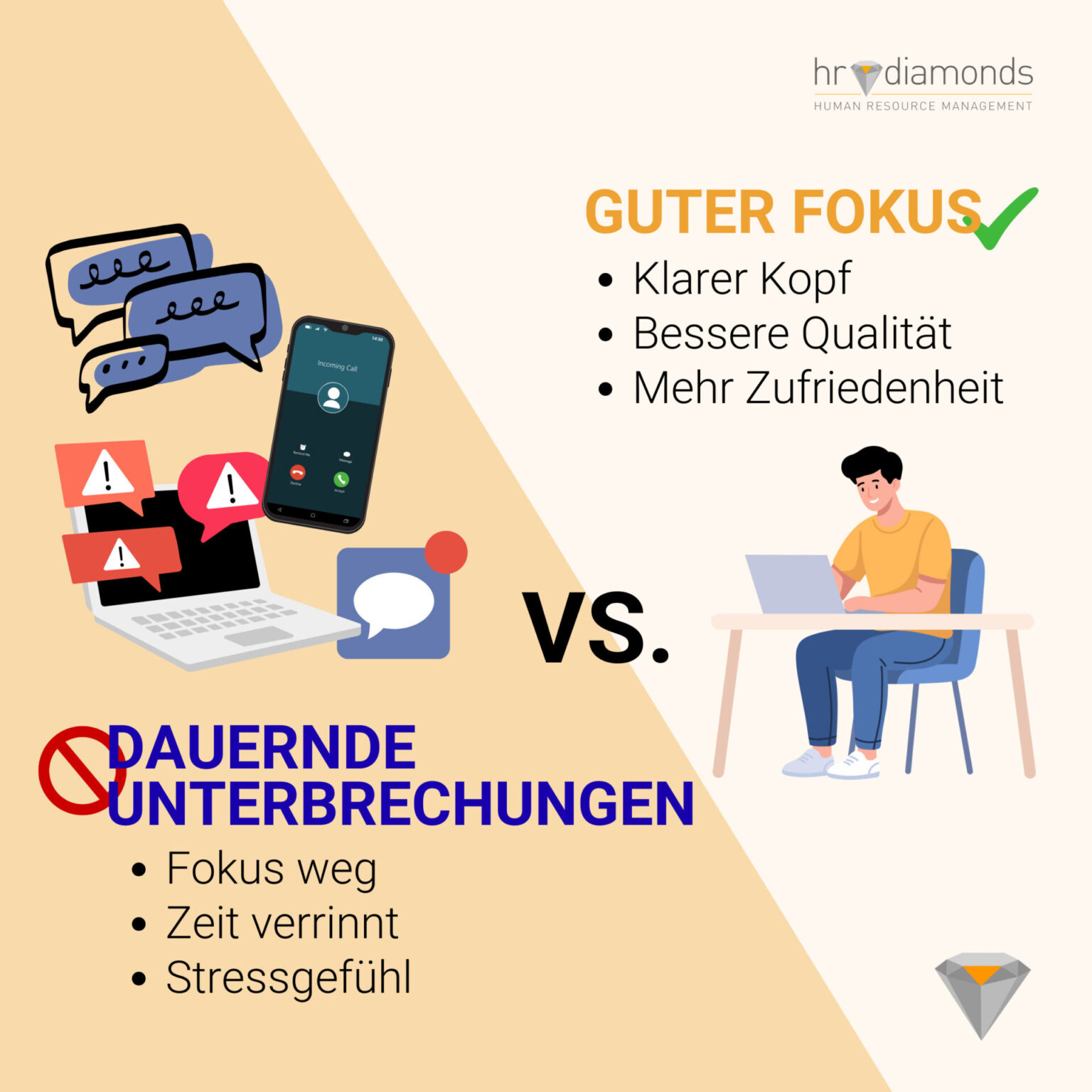

But what do these constant interruptions actually do to us? And what can we do to enable more undisturbed work?

Work interruptions as a stress factor

Studies show that work interruptions are among the most common stressors in the workplace [1][2]. In addition to the often immediately noticeable “annoyance” that these interruptions cause, they also have measurable effects. Among other things, interruptions lead to:

- slower completion of tasks

- delayed reactions in important situations

- and an increased error rate [3]

What is often underestimated is that the effects are not just short-term.

Effects on health and well-being

Frequent interruptions at work can also have a long-term impact on health and well-being. Job satisfaction declines and, in the long term, the risk of serious health problems increases [4]. Studies show, for example, a link between frequent interruptions and burnout and depressive symptoms [5].

But: Not every interruption is the same

At the same time, it is important to note that interruptions do not always have the same effect.Their impact depends heavily on the context, such as the type of activity or how and by what means one is interrupted [5].

This is also consistent with our own experience: sometimes a quick chat is welcome, especially when you may not want to deal with a particular task at that moment. 😉

Nevertheless, work interruptions remain relevant stressors that can have a negative impact on satisfaction and health.

What helps when dealing with interruptions?

In addition to stressors, there are also protective factors that can cushion negative effects. The following are particularly effective:

- Scope of action: for example, the ability to organize your own focus times

- Social support: being able to share tasks and not feel left alone [5]

For example, if employees can consciously create time slots for undisturbed work or are part of a supportive team, the negative effects of interruptions can be significantly reduced.

Specific starting points for practical application

At the organizational level:

- Raise awareness of work interruptions and their effects.

- Send non-urgent emails only at defined times.

- Set team- or organization-wide focus or quiet times.

- Establish clear rules for when interruptions are truly necessary.

At the individual level:

- Consciously disable notifications and, for example, process emails in batches at fixed times

- Enter focus times in your calendar and communicate them transparently

- Use noise-canceling headphones for peace and quiet and as a signal to others

... and also reflect on whether you really need to distract your colleague right now, or whether it can perhaps wait a little longer.

Conclusion

Work interruptions cannot be completely avoided. But they can be managed more consciously.A common understanding, clear guidelines, and individual strategies can help reduce stress and make it possible to work with greater concentration more often.

Quellen

[1] Baethge, A., Rigotti, T., & Roe, R. A. (2015). Just more of the same, or different? An integrative theoretical framework for the study of cumulative interruptions at work. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 24(2), 308–323. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2014. 897943

[2] BAuA. (2020). Stress report Germany 2019: Psychische Anforderungen, Ressourcen und Befinden. Federal Intitute for Occupational Safety and Health. https://www.baua.de/DE/Angebote/ Publikationen/Berichte/Stressreport-2019.html

[3] Sharples, S., & Megaw, T. (2015). Definition and measurement of human workload. In J. R. Wilson & S. Sharples (Eds.), Evaluation of Human Work (4th edition), 516–544.

[4] Stansfeld, S., & Candy, B. (2006). Psychosocial work environment and mental health—a meta-analytic review. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 32(6), 443–462. https://doi. org/10.5271/sjweh.1050

[5] Junghanns, G., Schütte, M., & Beck, D. (2025). Psychische Belastung im Berufsleben erkennen und Arbeit gut gestalten. Dortmund: Bundesanstalt für Arbeitsschutz und Arbeitsmedizin. baua: Praxis. Abrufbar unter: https://www.baua.de/DE/Angebote/Publikationen/Praxis/A45